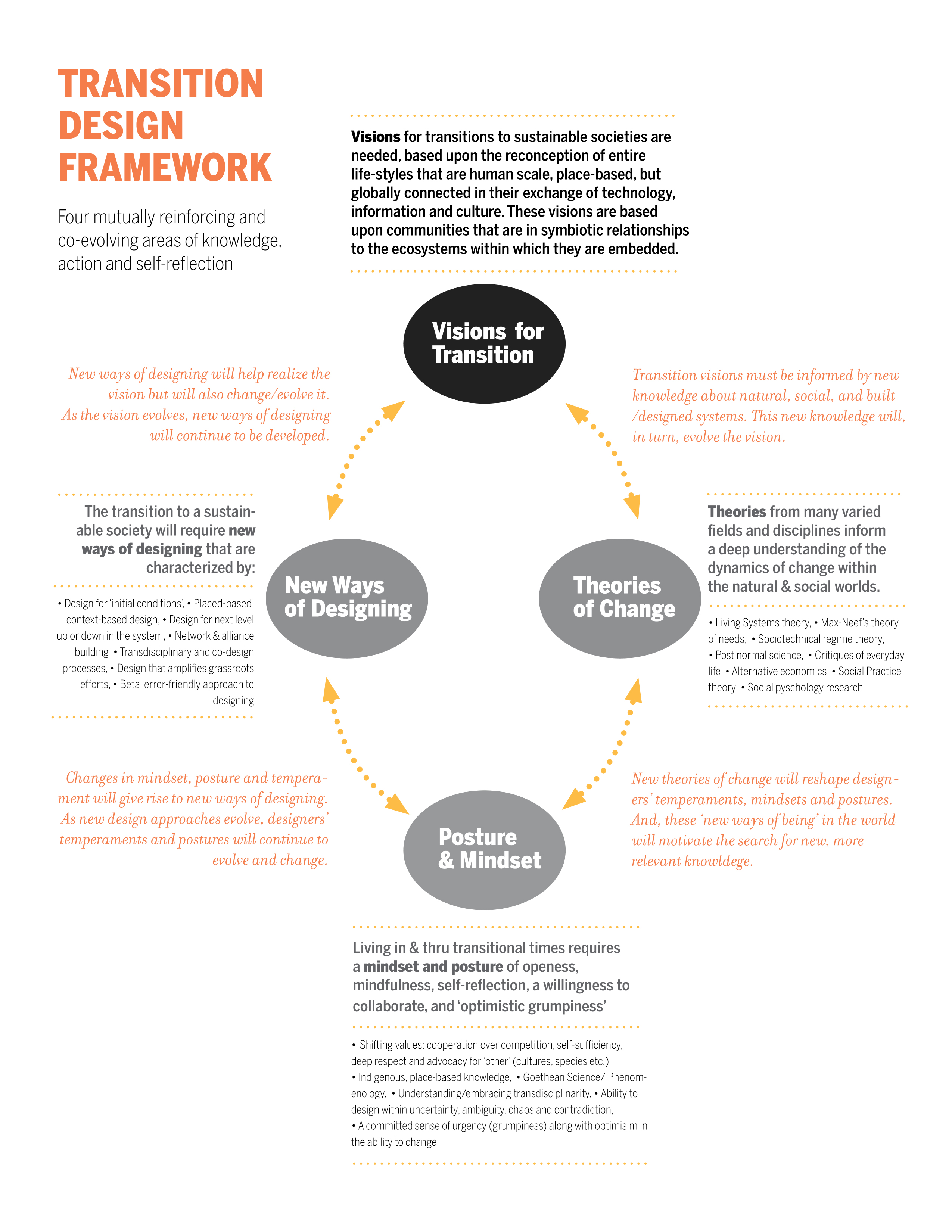

The Transition Design framework outlines four mutually reinforcing and co-evolving areas of knowledge, action and self-reflection: 1) Vision; 2) Theories of Change; 3) Mindset & Posture; 4) New Ways of Designing.

Transition Design proposes that more compelling future-oriented visions are needed to inform and inspire projects in the present and that the tools and methods of design can aid in the development of these visions. Tonkinwise (2014) argues for “motivating visions as well as visions that can serve as measures against which to evaluate design moves, but visions that are also modifiable according to the changing situation.” Dunne and Raby (2013) argue that visioning creates spaces for discussion and debate about alternative futures and new ways of being. It requires us to suspend disbelief and forget how things are now and wonder about how things could be.

Transition Design proposes the development of future visions that are dynamic and grassroots based, that emerge from local conditions vs. a one-size-fits-all process, and that remain open-ended and speculative. This type of visioning is a circular, iterative and error-friendly process used to envision radically new ideas for the future that serve to inform even small, modest solutions in the present. Visions of sustainable futures can provide a means through which contemporary lifestyles and design interventions can be assessed and critiqued against a desired future state and can inform small design decisions in the present.

Various design approaches have diversified our ability to imagine the future, and inspire short, mid- and long-term solutions. Examples include Critical and Speculative Design (Dunne & Raby 2013) and backcasting and scenario based initiatives such as Manzini and Jegou’s Sustainable Everyday (2003) and Jonathon Porritt’s The World We Made (2013).

Never in history has the need for change been more urgent (Max-Neef 2011). Yet, transformational societal change will depend upon our ability to change our ideas about change itself—how it manifests and how it can be catalyzed and directed. Systems-level, ongoing societal change is inherently transdisciplinary—it must be informed by ideas, theories and methodologies from many varied fields and disciplines. Theories of Change is a key area within the Transition Design Framework for three important reasons: 1) A theory of change is always present within a planned/designed course of action, whether it is explicitly acknowledged or not; 2) Transition to sustainable futures will require sweeping change at every level of our society; 3) Our conventional, outmoded and seemingly intuitive ideas about change lie at the root of many wicked problems (Irwin 2011; Scott 1999; Escobar 2011).

A new, transdisciplinary body of knowledge is emerging that explains the dynamics of change within complex systems and challenges our current paradigms and assumptions. These ideas have the potential to inform new approaches to design and problem solving. Ideas and discoveries from a diversity of fields such as physics, biology, sociology and organizational development have revealed that change within open, complex systems such as social organizations and ecosystems manifests in counter-intuitive ways. And, although change within such systems can be catalyzed and even gently directed, it cannot be managed or controlled, nor can outcomes be accurately predicted (Capra & Luisi 2014; Wheatley 2006; Meadows 2008; Brigs & Peat 1990; Prigogine & Stengers 1994). The Transition Design Framework is a fluid, evolving body of knowledge and ideas, often from outside design, whose objective is to provide designers with new tools and methodologies to initiate and catalyze transitions toward more sustainable futures.

Living in and through transitional times calls for self-reflection and new ways of ‘being’ in the world. Fundamental change is often the result of a shift in mindset or worldview that leads to different ways of interacting with others. Our individual and collective mindsets represent the beliefs, values, assumptions and expectations formed by our individual experiences, cultural norms, religious and spiritual beliefs and the socioeconomic and political paradigms to which we subscribe (Capra 1997; Kearney 1984; Clarke 2002). Designers’ mindsets and postures often go unnoticed and unacknowledged but they profoundly influence what is identified as a problem and how it is framed and solved within a given context. Transition Design asks designers to examine their own value system and the role it plays in the design process and argues that solutions will be best conceived within a more holistic worldview that informs more collaborative and responsible postures for interaction. Transition Design examines the phenomenon of mindset and worldview and its connection in wicked problems (Kearney 1984, Linderman 2012; Tarnas 2010; Capra and Luisi 2014; Irwin 2011a).

The transition to a sustainable society will require design approaches informed by new and different value sets and knowledge. Transition Designers see themselves as agents of change and are ambitious in their desire to transform systems. They understand how to work iteratively, at multiple levels of scale, over long horizons of time. Because transition designers develop visions of the ‘long now’ (Brand 1999), they take a decidedly different approach to problem solving in the present. Transition Designers learn to see and solve for wicked problems and view a single design or solution as a single step in a longer transition toward a future-based vision. Some solutions have intentionally short life-spans and are designed to become obsolete as steps toward a longer- term goal. Other solutions are designed to change/evolve over long periods of time. Transition Designers look for ‘emergent possibilities’ within problem contexts, as opposed to imposing pre-planned and fully resolved solutions upon a situation. This way of designing must be informed by a deep understanding of local eco-systems and culture.

Transition Designers work in three broad areas:

1. They develop powerful narratives and visions of the future or the ‘not yet’ (Bloch 1995; de Sousa Santos 2006).

2. They amplify and connect grassroots efforts undertaken by local communities and organizations (Penin 2013; Manzini 2007, 2015). Service design or social innovation solutions can be steps within long-term transition solutions.

3. They work in transdisciplinary teams to design new, innovative and place-based solutions rooted in and guided by transition visions.

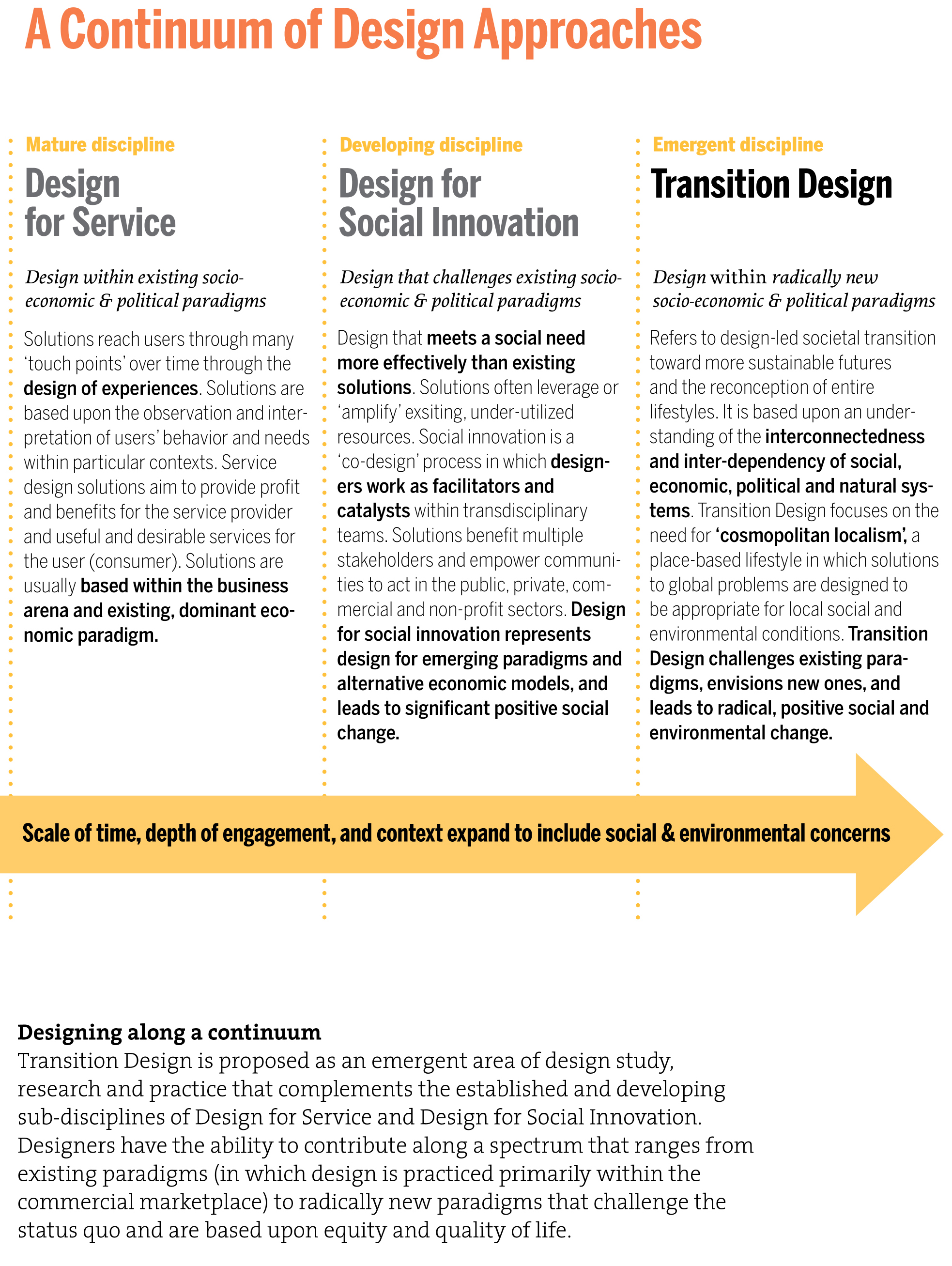

Although we consider Transition Design to be a distinctive way of designing, it is complementary to other design approaches such as design for service and design for social innovation. Transition Design requires a commitment to ongoing learning and personal change as well as the tenacity to change a system through multiple, iterative

interventions over time.